At Paris Kadist Art Foundation an experimental format, based on cooperation between scientists, artists and members of the local community, analyzes how species inhabit an area and alter the natural and cultural space of the other species in the Tierra del Fuego.

You step off the narrow Rue des Trois Frères in Paris, with all its picturesque Montmartre ateliers and cafés, and cross the threshold of the Kadist Art Foundation to find yourself in the Karukinka Park, on the Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego.

After years of deforestation by a company logging timber for the international market, the island is now protected by an NGO called the Wildlife Conservation Society, directed in Chile by biologist Bárbara Saavedra. She launched the Ensayos artistic-scientific research project with the curator Camila Marambio in 2011.

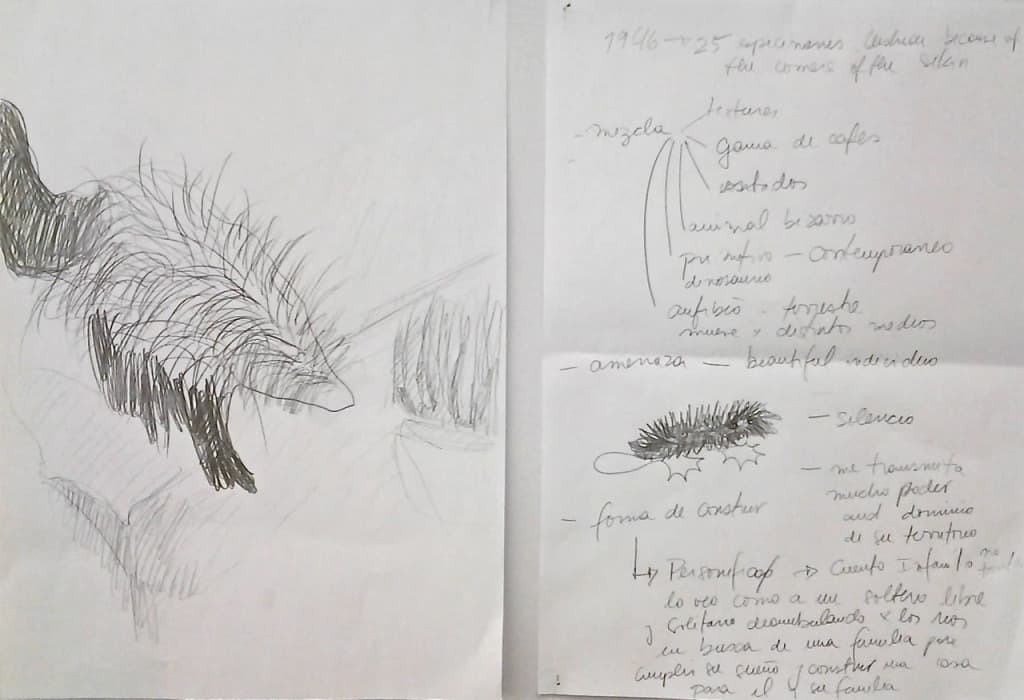

Its experimental format is based on cooperation between scientists, artists and members of the local community and takes the form of short group residencies focusing on the themes determined in the initial island observation phase (Ensayo #1). One of these is the programme to eradicate the castor Canadensis, imported by the Argentine government in the 1940s. It has colonised watercourses and built dams and embankments that are veritable works of modern civil engineering, causing further forest decline and upsetting the ecosystem. This multidisciplinary analysis of beaver life on the island has produced an exhibition called Beyond the End (Ensayo #2).

As well as Derek Córcoran (ecologist), Giorgia Graells (biologist), Émilie Hache (philosopher), Myriam Lefkowitz (performer), Carla Macchiavello (art historian), Laura Ogden (anthropologist), Alfredo Prieto (archaeologist), Maria Prieto (urban and biodynamic farmer) and Sofia Ugarte (sociologist), the artists Christy Gast, Fabienne Lasserre, Amanda Piña, Carolina Saquel, Maria Luisa Murillo and Geir Tore Holm & Søssa Jørgensen were involved in the Paris phase of the project. Beyond the End starts progresses from the “invasion” concept to that of the “diaspora”, overturning the way the issue is addressed: no longer scientific, it becomes relational and observes – from a non-human angle – how species inhabit an area and alter the natural and cultural space of the other species.

The group looked beyond the separation into species and discipline, morality and abjection, artistic authorship and collective project to create two environments, one immersive-emotional and the other of exploration. In them, installations, performances, videos, photographs and study material help visitors learn about the reciprocal relationship between human life and that of a harmful animal; these seem to meet in the video Conjuring via the performative actions of Christy Gast, following the sculptured form of the embankment built by the beavers.

The exhibition route begins with an experience of the location, in a typical local home, where you have conflicting sensations: the Castor Chef documentary shows a castor being captured, skinned and chopped up by a park ranger in a collective celebration; the Castorera (A Love Story) fictionreproduces moments in the rodents’ life as a pair featuring the idyllic love-nature combination used by humans to construct an image of the ideal world; María Luisa Murillo uses a nostalgic photograph of an old pier, Vestigios del muelle de Caleta María, to work on her memory of her great-great grandmother, a Swiss emigrant who founded the largest timber industry in Porto Yartou.

The half-light of the room and the informality of a human home are countered by the muffled sounds and oneiric images of the beaver’s semi-aquatic life – as unstable and fluctuating as that of the humans with whom it shares the fight for survival. Looking at the Dreamworlds of Beavers video and listening toSpeculative Wonder, a text written by anthropologist Laura Ogden on the concept of political ecology, you enter into symbiosis with the animal’s world, which becomes your own for a few minutes.

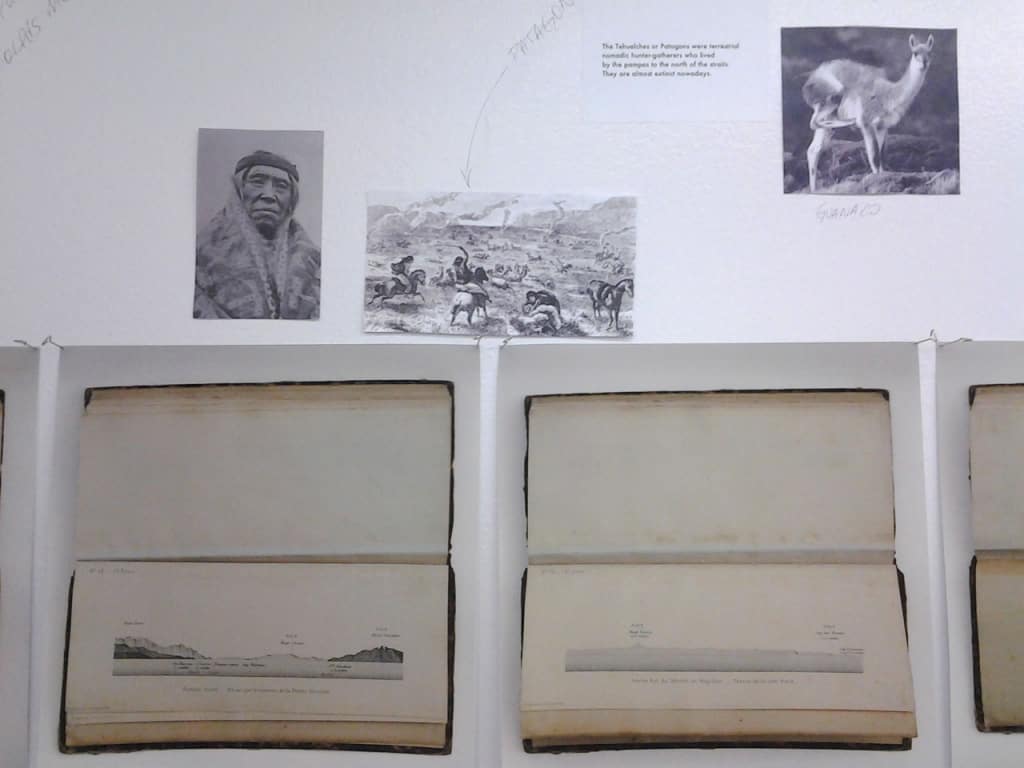

Paris, the city that showed nine “specimens” of Selk’nam – the indigenous people of Tierra del Fuego – in a “human zoo” at the 1889 World’s Fair, establishing the image of uncivilised indigenous cultures versus the European concept of modernity(actually coined by a Nicaraguan poet in 1890, as Timothy Mitchell writes [1]), is today experimenting with a concept of the future based on an emotional relationship between species and on social reorganisation in natural space, starting with the discovery of an old link that cannot be predetermined by the Rationalist vocation of the cartographic grid: as Benoit Hické explains during the performative lecture Inside the Beaver’s Skin,the Musée d’Histoire Naturelle was built on La Bièvre, covered over in the 19th century, a name that originates etymologically from beaver.

1 Timothy Mitchell, Questions of Modernity, Minnesota, University of Minnesota Press, 2000, p. 1-7.

© all rights reserved