Members of the Australia, Chile and northern European pod gathered to learn, share and play in the peat of magical Minjerribah on the east coast of Australia. Before soaking into the details of this patterned fen foray, I would like to acknowledge the reason we were able to see, feel, smell, drink in and learn from these unique wetlands.

Our peat is here today thanks to the dedicated, intricate, holistic, and integrative care for Country provided by Quandamooka peoples since time immemorial. I live and work and have the pleasure of learning from many parts of Quandamooka Country, from the leaves and bubbles and from the knowledge holders and protectors of land who carry these precious things. No words on a screen can capture my sense of gratitude and privilege, all I can do is try to show it in the way I hold Country in my life, and work to protect and integrate it in diverse ways. Ways that reflect that I am a first-generation migrant, my connection to this place can only ever be as deep as those surface layers of living plants above meters of deep, dense, rich peat, but I can learn of and imagine the richness below and show respect for its role in holding all of us occupying this surface layer for our short time.

—————

I am Renee Rossini, one of the members of the Australian pod. I am an ecologist who has soaked her feet in many types of unique wetlands in so-called Australia for the last few decades. I am also an artist and educator. I see ecology, and my place as a queer ecologist, as a science of weaving and transcending or blurring the lines between things – science/art, human/non-human, teacher/learner. For me, ecology is serving a purpose – a lens to understand, cherish and communicate the rich narratives that exist around us, especially those that are overlooked or we are at risk of losing. My membership in Ensayos comes from this place.

For this blog, I was given the honor of documenting our collective experience. I felt like I wanted to capture some of our learnings, our journeys of discovery and our discussions. I wanted something less structured than an essay; it didn’t feel true to the sense of play and discovery we held as a group during our time. Of all the scrawled drawings on napkins, and in sand, and on whiteboards trying to capture the ideas. I sat with myself and pulled from the peat some key messages, or learnings, I felt we looped and returned too. And given our time was on Minjerribah, on this very unique type of peat, I wanted to try and capture some of the things that our peat brings to the Ensayos table. I felt drawn to document these things through words, pictures, maps. And I want to string them together into something (hopefully) coherent.

What I love about Ensayos, its philosophy and our shared practice, is that everything is a process, a journey. There is no room full of canvases at an opening event, there is no final show, or sale. I owe Freja Carmichael so much for teaching me about this over our years together. There are core themes – a heuristic – and core places – bogs, mires, fens, peat. And it’s how we are all playing with and interacting with those things that we try to capture and communicate. In the spirit of this, I’ve tried to alleviate the pressure on myself to ‘complete’ something. And instead, to ‘document’ something, capture a tiny view through a window of a much larger structure that is only partially visible.

——————

THE NARRATIVES OF QUANDAMOOKA COUNTRY WATER

It’s easy to forget how unique Minjerribah and the broader sand island system is. You can be driving up a hill, distracted by the glittering sea, and forget that the slope you are climbing is the face of an ancient dune. And below the bitumen, and scribbly-bark litter, is nothing more than sand. No bedrock, nothing solid. Just sand. It could shift – if we sit in deep time, it has shifted a long way. Its solidity now comes from its crust of plants, and people.

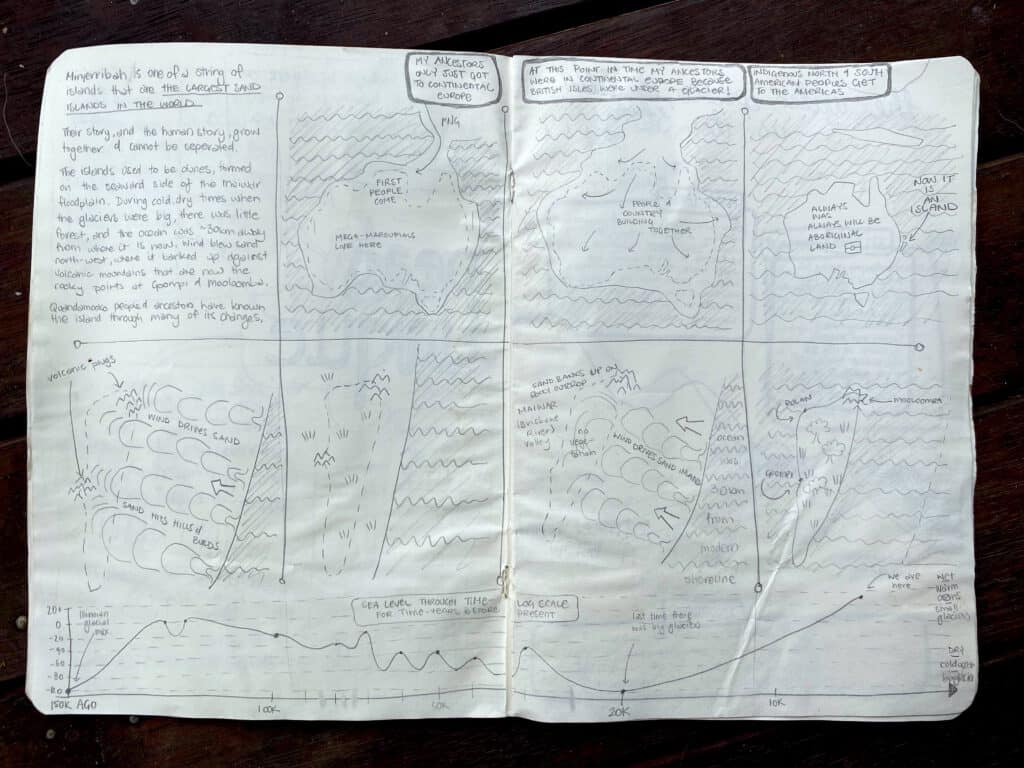

Explaining how so much sand came to be in this place requires some big spatiotemporal thinking. I have attempted to capture so many things at once – on the bottom, how the sea has risen and fallen over the past 150 thousand years, because Quandamooka Country is sea and land, they are inextricably tied, they are not separate beings. In the centre, how that shifting of the sea made way for the shifting of sand. How ancient volcanos and coastal breezes worked together to build immense dune fields that are so old we forget we are standing on giant sandhills. And on the top of the page, how that shifting of coastlines created the shifting of people, and how I can relate to the deep connection of First Nations people as a European migrant, how I can remind myself of where my ancestors were on the other side of the planet through all this shifting sand.

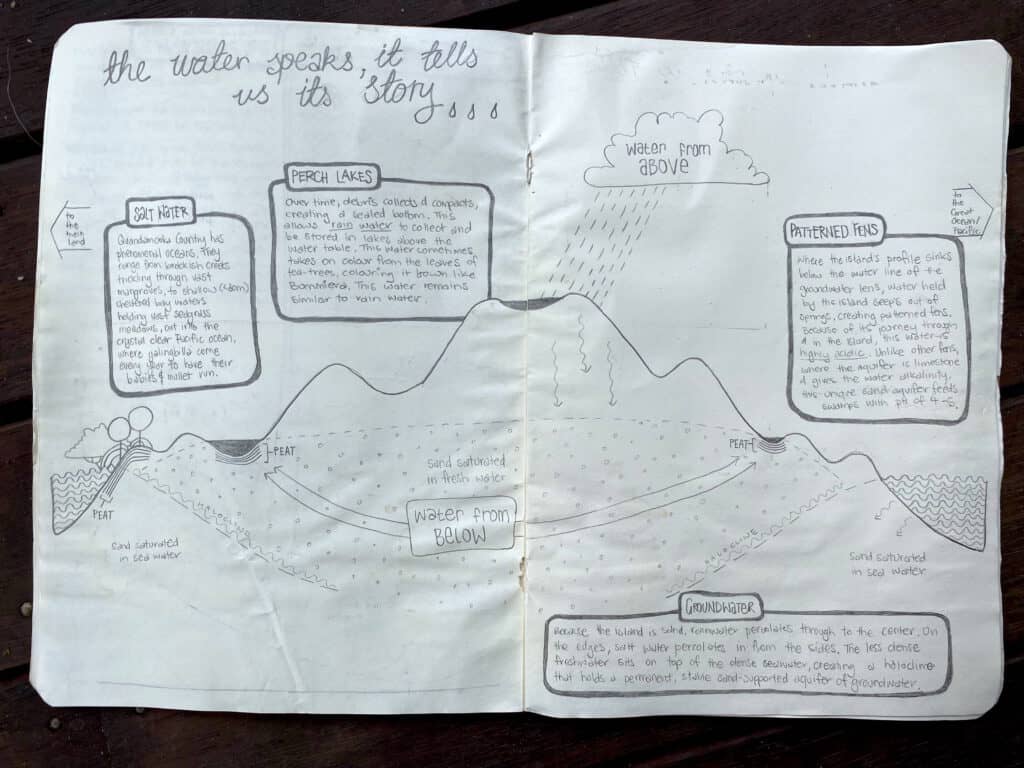

After driving up the dune, you come to a lake. And if you drive on, you come to a fen. Or if you are craving an ice-cream and the wind in your hair, you swoop through the ‘S-bends’ and smirk as Country opens up into a heathy, low laying area – the patterned fens. There are many kinds of water on the sand islands, and each type holds a different story, has followed a different path, and because of that brings different things to the table. If we listen to it, and watch it, it’s easy to see the differences and what they create.

——————

OUR PEAT, YOUR PEAT

The beauty of this trip was we had holders of peat from three very different places, each with different links. We are still in the early stages of getting to know each other’s wetlands, but we are engaging all of our senses to share. We have different commonalities; Tierra del Fuego and Quandamooka both share legacies of Gondwanan connection, Finland and Norway and Tierra del Fuego share cool climates we in Quandamooka Country cannot know.

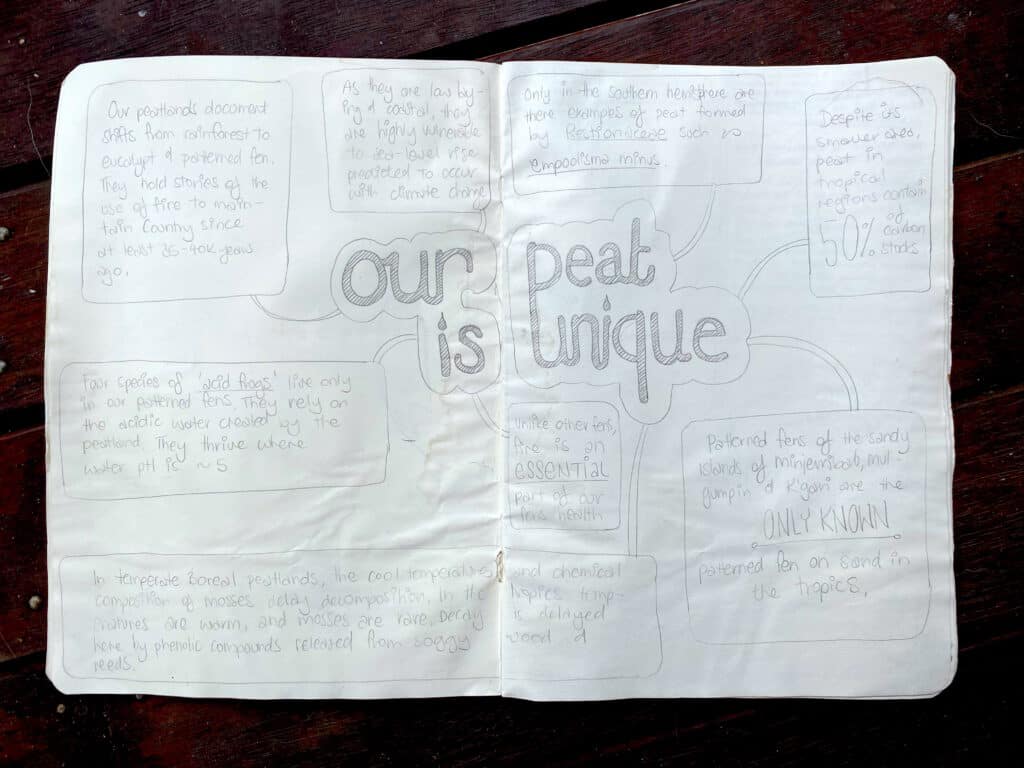

The peat we meet on is unique. It is formed within a fen – where the water that feeds it comes from the ground, not from the sky. Many fens are fed by calcareous aquifers that lend alkalinity to the water. Our fens are fed by aquifers on sand, with the water that enters them already holding acidity from its journey. Prof Cath Lovelock and team at The University of Queensland have measured water held within the island (i.e. before it comes to the swamp) at pH 5. It then becomes more acidic when it percolates through the fen. Our peat is built from vascular plants, not mosses like Sphagnum. Our peat builds in the tropics, where the warm weather should promote bacterial activity and decay so fast that peat won’t build. Instead, acid, phenols and lack of oxygen slow decomposition. I tried to capture some of the ways we talked about this peat being unique.

Imagine the heath. Short, spiked plants encrusting the sand. We creep through it, we want to be IN IT, not just peek at it from the edges. We find a channel in the fens by listening to where the water rushes.

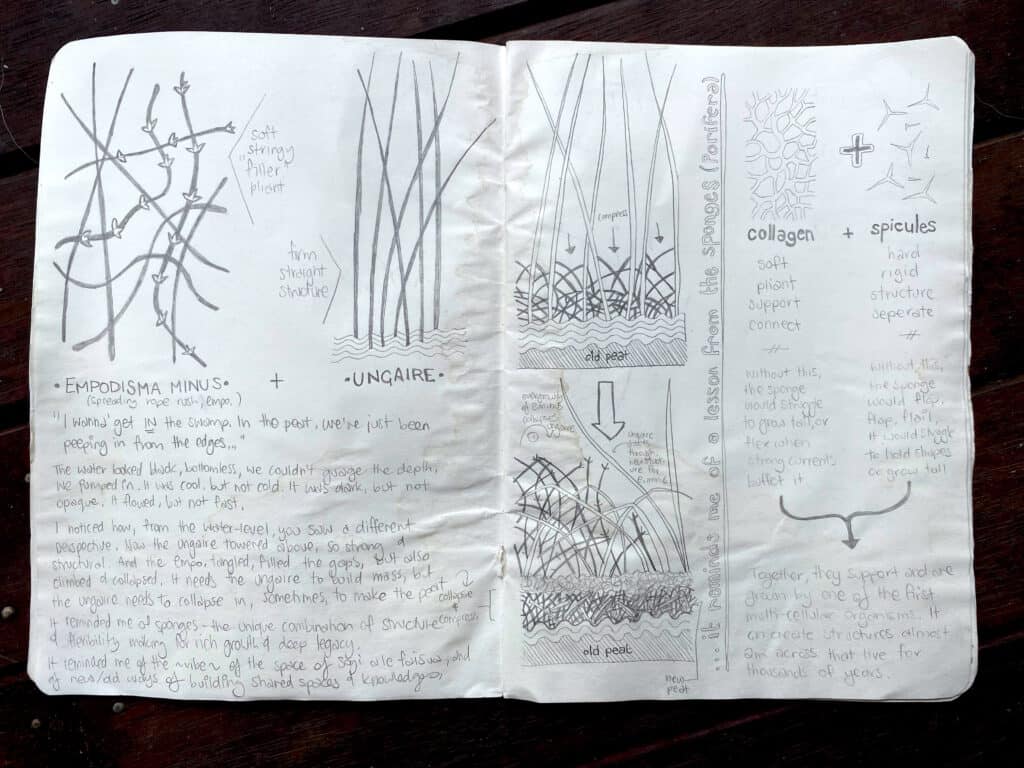

We plunge in. We drift with the current. We get a view from the water’s perspective. We can feel the peat, we can touch it, squeeze it, caress it. From the water, you can see how our Quandamooka peat builds. We have sphagnum here too – we are still searching for it but struggling to find it. Our peat is built by vascular plants, by reeds and sedges. In particular, a sedge called Empodisma minus. But it doesn’t act alone, it clambers over and fills the spaces between so many other plants – banksia, saw sedge, and Ungaire.

Ungaire is such a pinnacle of our time with peat on Minjerribah. We sit on the Carmichael balcony, listening to the Great Ocean and fondling Ungaire that is drying. Sonja and Leecee will turn this strong and subtly coloured fiber into bags, baskets, mats, knowledge, and connections. Our gifts to the pavilion in Venice were held by Ungaire nets woven by Sonja. We ask why some Ungaire is pinker than others, and want to work to relearn this, because pink is such a beautiful colour. So much of our learning, speaking and adventuring centres on this plant. Tall, firm, and subtle. Floating in that channel, I thought a lot about how building our peat needs both the soft, filling, spongy elements made by Empodisma AND the firm, structural elements of the Ungaire. And how that is a lesson you can learn from other organisms, and from us.

——————