WHEN

September 10 – 28, 2019

WHAT

After the opening of our exhibition, Everything is Possibly an Oracle, we headed to the central highlands, traversing thirsty country on high fire alert. Guided by our friend, Dale Harding, we accepted an invitation from Carol and Trent Vincent, who are custodians of Saddler’s Springs, an 8100ha property nestled between Carnarvon Gorge and Mt. Moffat National Parks. We were hosted at Junjuddie Flats, an eco-centre originally set up by the landowner for wilderness programs engaging disadvantaged youths and now occasionally used for wilderness retreats.

Feeling the junjuddie, undine and our guides – the ancient zamias, a hairy caterpillar, playful birds and purple darling peas – we clambered the slopes in search of the northernmost headwater of the Murray-Darling Basin. Finding the source evoked more questions than answers. Where does the water that seeps from this mossy crevice come from? Where does it flow to? What waters move beneath us? How does it connect to the sea? And so, filled with curiosity of hydrological lines and underground reservoirs, we returned to our camp, singing the creek along the way.

Carol and Trent shared their love and deep respect for the land and their fears that the pending sale of the property will lead to an eco-resort and a type of tourism that disregards what is sacred. We brainstormed ways in which it could remain in their care, questioning mechanisms of land ownership and national parks, discussing collectivity, responsibilities and access, and highlighting the rights of the traditional custodians, the Bidjara people. They spoke of a 200-year plan, even a 500-year plan – a plan that shifts the focus from short-term human benefit to long-term needs of all non-human life and spirit inhabiting the property.

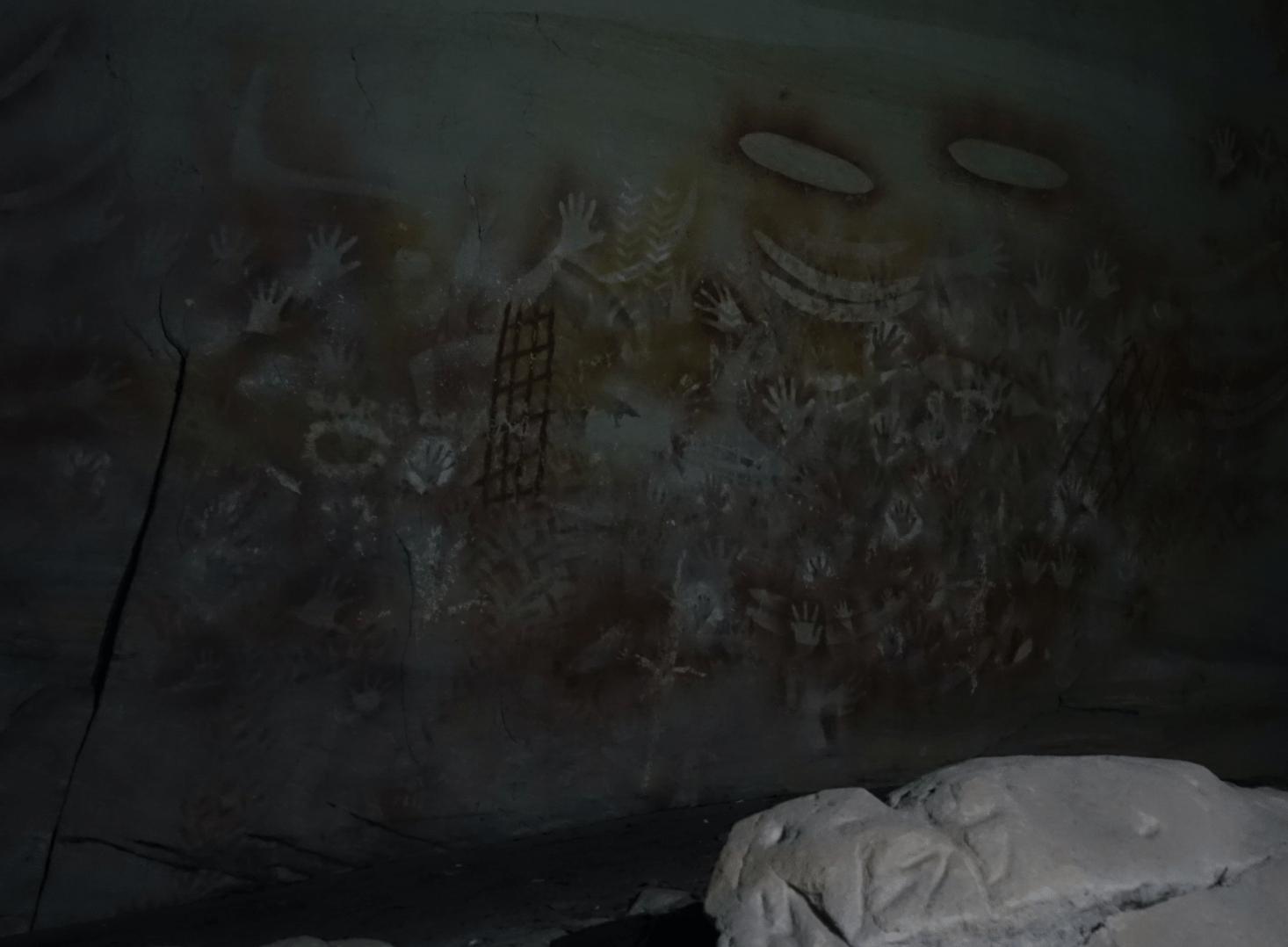

With futures beyond our lifetime in mind, and feeling the tug of full moon, we sought the ritual knowledge of birth and death present in Carnarvon Gorge. Whilst we seemed to be the only humans in the gorge that night, we knew we were not alone as we criss-crossed the sinuous creek and attuned our senses. Sounding our presence, hands welcomed us to the vulva – the origin – repeated amongst stories painted and carved into the sandstone walls.

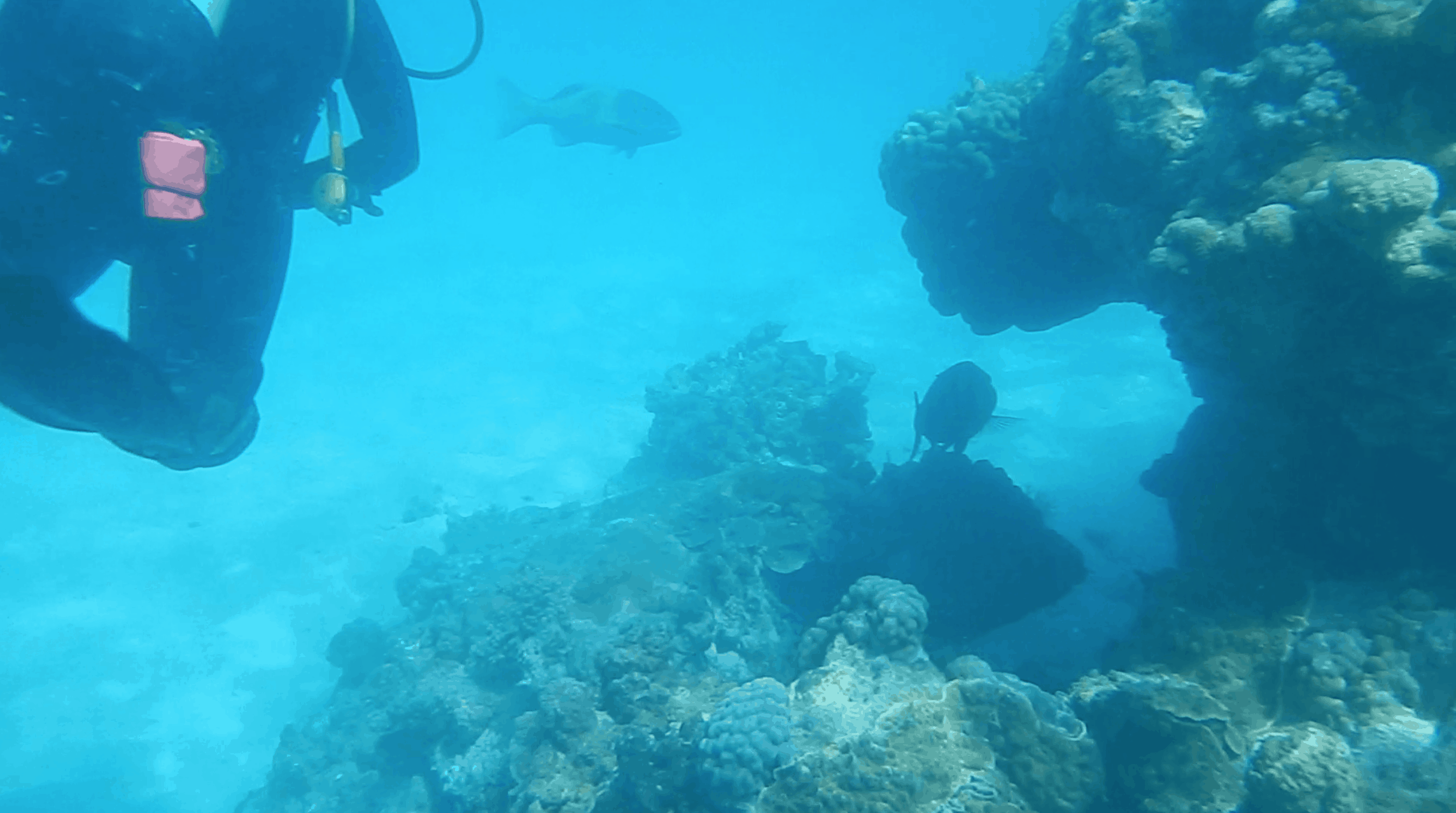

Further north, in the wet tropics, we took the opportunity offered to us by our newest collaborator, ichthyologist Lynne van Herwerden, to spend some days at a rainforest-clad property near Ingham, swimming waterholes and navigating the creeks flow, negotiating ‘wait-a-while’ vines and diversions along the way. Here we rehearsed ‘slowing down fast’, becoming a ritual of water, buoyant bodies and laughter that was re-performed with collaborator Cecilia Vicuña at Errant Bodies Studio in Berlin.

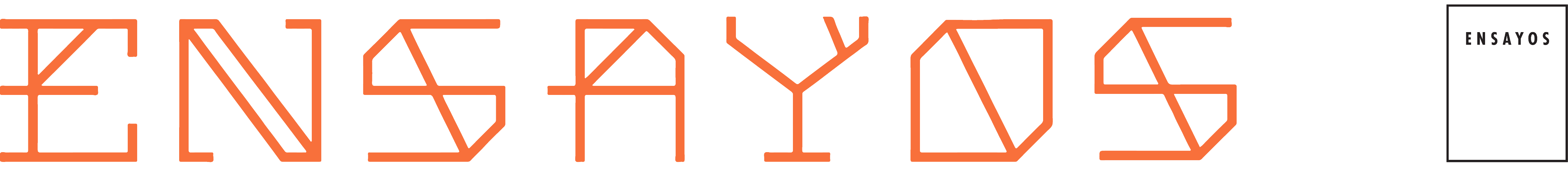

Feeling our way into the underwater world that concerns us, we joined Lynne at her home on Yunbenun (Magnetic Island) learning how to SCUBA, snorkeling the Great Barrier Reef, sailing offshore to sight dolphins and turtles, and walking its national parks to understand the relationality between sea and land conservation. Our nights were spent discussing Lynne’s academic research, her family’s activism, and the spirited force that will fuel Ensayos’s response to the challenges that Lynne’s research has made visible. Playfully rehearsing how to communicate the threats being faced by the bottom of the food web (phytoplankton), we also spent time at James Cook University’s Green (Screen) Room.

Gaining confidence in our newly-formed fins, we continued snorkeling with local artist and curator of the Bundaberg Regional Gallery, Anita Holtsclaw, along the shore reef at Barolin Rocks, near Bargara. Inspired to go deeper, we ventured offshore to Wallaginji, a word that means ‘beautiful reef’ to traditional custodians of the region, the Tarebilang Bunda, Bailai, Gooreng Gooreng, and Gurang people. Some of our group strolled the coral cay, learning of its formation by wind, waves and shifting coral rubble and how it is held together by a sticky web of birds, insects and pisonia trees. Others dove into the calm lagoon and then into the shifting currents of the outer reef, sighting a Wobbygong shark, an orgy of sea turtles, and hearing the call of the humpback whales returning south with their young. Questions of the impacts of tourism on the Great Barrier Reef, the attitudes with which tour agencies operate, followed us along the coastline as we participated and observed.

Cooran, our final destination before circling back to the city, offered a quiet valley at the base of Pinbarren Mountain, where we paused with our origins, questions, feelings and practices – tuning, tarot, singing, writing, poetry, flower essences, cyanotype, video and field recording.

WHY

Fires are burning.

Because the Great Artesian Basin was once sea and the Murray-Darling Basin meets the southern coastline. Because the land is salty and dry and, still, trees are being bulldozed and water is being diverted.

To trace the flows of water from sandstone ranges and tropical rainforests to underground reservoirs and the complex systems of rivers, creeks and streams. Because meeting and acknowledging the source of our waters is a step toward understanding what waterways need and how to act with and for water.

To learn about reef health, the effects of microplastics and climate change in the ocean and what scientist Lynne van Herwerden and her colleagues at James Cook University in Townsville, QLD are doing about it, in advance of the collaboration that the Australian pod of Ensayo #4 has initiated with the inhabitants of the Coral Reef and its custodians.

Because 5, 10, 30-year plans are inadequate to address environmental issues that present long term risks to the earth.

The pumice stone is approaching.

WHO

Caitlin Franzmann, Christy Gast, Camila Marambio, Lynne van Herwerden, Anita Holtsclaw, Carol and Trent Vincent.

HOW

Big Mama, the van that got us places.

Camping in backyards and bush retreats through the generosity of our hosts.

The Queensland Government through Arts Queensland funded our travel and research.